Yurei

Nagasawa Roshū / Paintings

- Contact Us

-

Material

Ink on paper, mounting ion silk

-

Size

115 (h) x 27 cm

-

Period

Edo period

-

Published

"Supranatural" by Galerie Mingei

Description

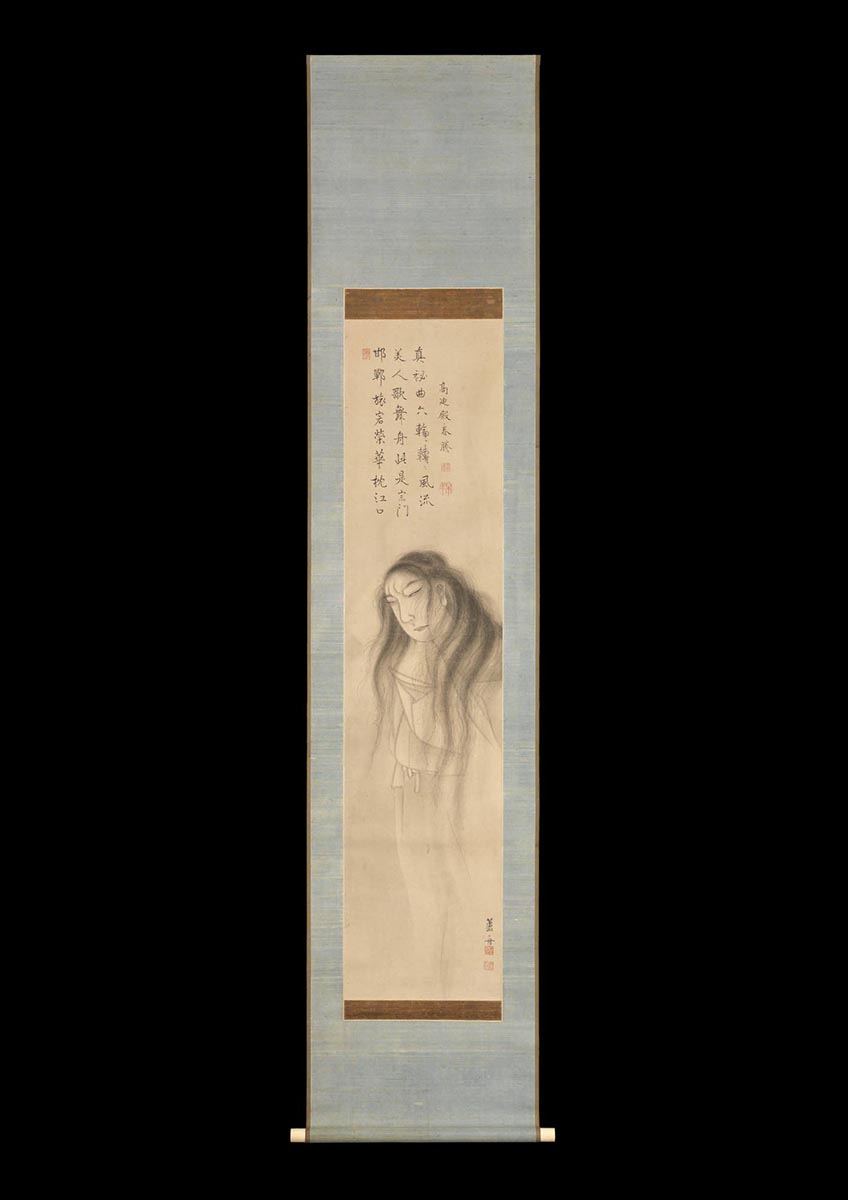

Yūrei - Ghost

Nagasawa Roshū (1767-1847)

Nagasawa Roshū was a painter of the late Edo period. He was adopted by the Maruyama School painter Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799) who created many large-scale paintings. Maruyama Ōkyo (1733-1795) was famous for his yūrei paintings without legs. It is easy to imagine that Nagasawa Rosetsu and his successor Roshū would thus have followed suit and produced ghost paintings in a similar style.

In this painting, a beautiful woman in a white kimono (kyō katabira: shroud) appears to float as she has no legs. Thin black ink applied with a steady brush touch is used overall. Her disheveled hair, her frown and the manner in which she bites her lower lip all express her suffering and her deep sorrow.

The poem refers to the ghost which represents the vanity of life. It suggests the Nō “Kantan” and “Eguchi”, which both connote the Heraclitean concept of “panta rhei” that denotes flux and the transitory nature of life. The poem itself refers to the supposed individual that Ikkyū Sōjun (1394-1481, a well-known Zen priest) sent for upon the death of On’ami Kanze Saburō Motoshig (1398-1467, the third chief of the Kanze School of Nō). This story first appears in Shiza yakusha mokuroku which was published in 1653, so this scroll was created after that date. It is read left to right.

“The traveler at Kantan had the pillow of wish fulfillment. The beauty Eguchi danced on the boat. That is the true hidden piece of the sect (this may suggest a School of Nō). The six phases of truth of the Noh play passed down with elegance Takamichi(?) wrote in the 3rd month.”

“A Dream of Kantan” is based on a classic Chinese story. In 719, a young man called Rosē passed through the region of Kantan (Believed to be the Chniese city of Handan in Hebei Province) dreaming of achieving success while on his way to the capital. He met a Taoist at the hostel, and they spoke at length. The Taoist gave him a pillow which was said to make dreams come true. Rosē slept on it, and had a dream in which he became successful, was later imprisoned under false charges, and when once again trusted by the king had a beautiful wife and three children before finally dying of old age. Upon awakening from the dream Rosē was still in the hostel with the Taoist. Rosē thanked him telling him that he had now seen all the ups and downs that life could hold, and that his overwhelming ambition had been tempered. Rosē then returned to his hometown.

“Eguchi” is based on the story of a beautiful prostitute and Saigyō, a well-known Buddhist monk. In 1167, Saigyō was on a pilgrimage. When he was passing through the Eguchi region, the heavens opened with rain and unleashed a powerful storm. He encountered the prostitute and asked to spend the night with her. They exchanged poems and she finally allowed Saigyō to stay. They established a friendship which endured for a long time.

It was said that Ikkyū wrote the Nō play “Eguchi” and that he gave it to the Noh actor Komparu Zenchiku (1405-1470). It is currently believed that the piece was originally written by Kan’ami, and passed down to his son Zeami who established Nō as an art, and that it was then transmitted to Komparu Zenchiku. The theatre piece narrates a later part of the story. A monk on a pilgrimage passed through the Eguchi region. He recalled the poem of Saigyō and recited it. Suddenly a woman came forward and apologized about the incident with Saigyō. She was the ghost of the prostitute, identified herself as Eguchi-no-kimi, and then disappeared. The monk decided to pray for her. In the evening, while he was chanting, Eguchi-no-kimi appeared on a boat, dancing and singing. She was finally transformed into Samantabhadra and went off into the western sky.