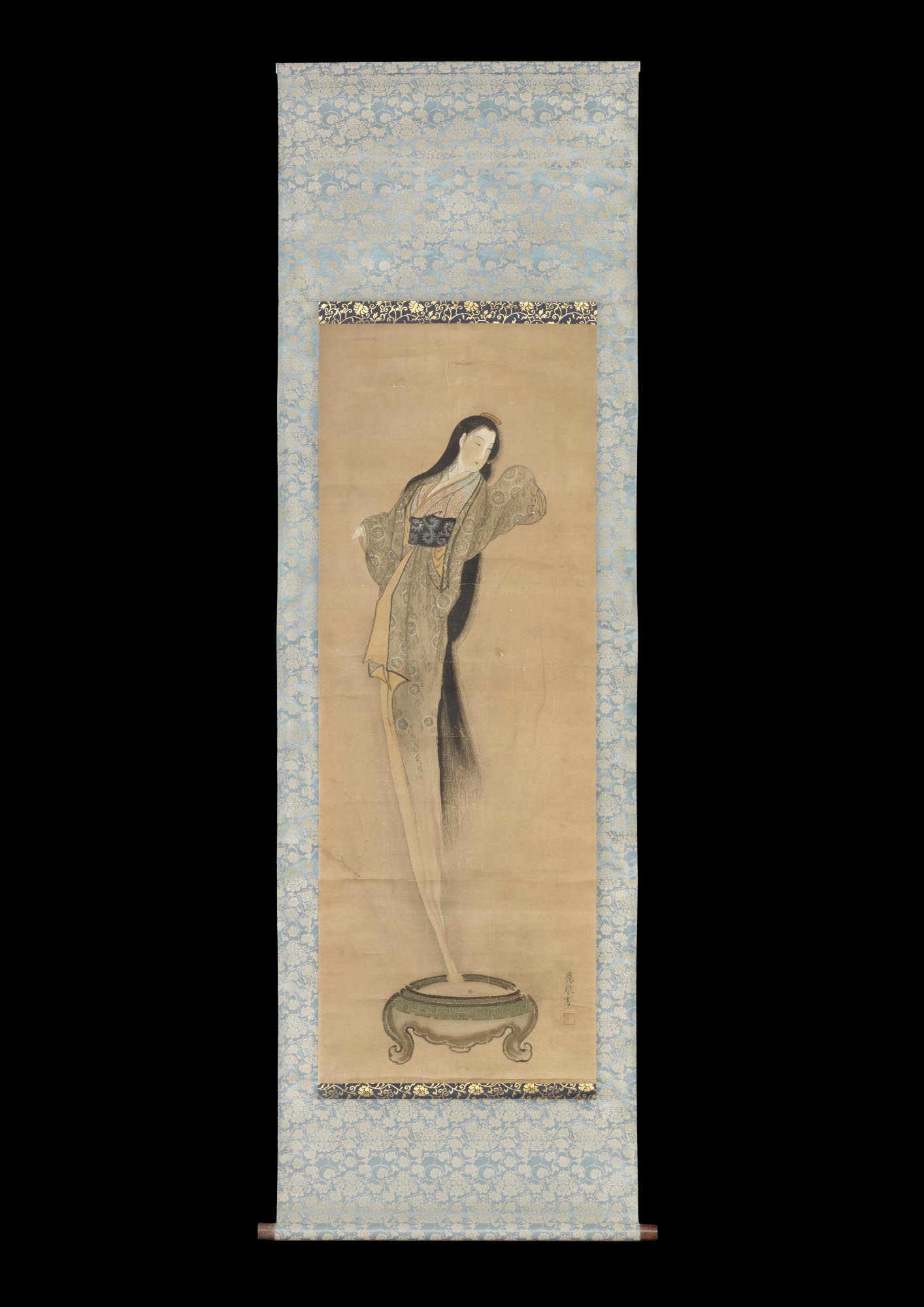

Yūrei

Maruyama Ōkyo / Paintings

- Sold

-

Material

Scroll, ink and colour on paper, mounting on silk

-

Size

121 (h) × 44 cm [186 (h) × 57,3 cm]

-

Published

"Supranatural" by Galerie Mingei, 2018

Description

Attributed to Maruyama Ōkyo (1733-1795)

This painting is based on a Chinese story which came to Japan with a poem by Bai Juyi (772-846). It became a classic in Japanese literature. The story tells of Emperor Wu of Han who had a beautiful wife named Li. Emperor Wu adored her, but she passed away very young. Li was unwilling to show her emaciated face to Emperor Wu during her illness, so they never saw each other until her death. Emperor Wu was left with the image of the beautiful young Li, was overcome with sorrows, and missed her terribly. One day, he

asked a Taoist to prepare a magic incense that could bring back the soul of a deceased person. This incense was called hangon-kō - the “incense which returns a soul”. Whenone night he lit it in his gold censer, Li’s silhouette appeared in the rising smoke. Nothing more than her silhouette became visible though as the incense burned away, so his broken heart never healed after all.

By the Edo Period this story had become widespread and was repeatedly mentioned

in Japanese literature. Many variants of it existed as well, including the Kabuki play Keisei

hangon-kō, originally a jōruri play, and the Ugetsu monogatari. The reason that the ghost scrolls became popular was that gatherings at which horror stories were told became popular in the An’ei era (1772-81), especially as a summer time activity, ostensibly to help people “cool off”.

Hanging scrolls depicting ghosts consequently became sought after as interior design elements as well. After Ōkyo introduced the “legless style”, it became very successful. An example of it is the hangon-kō no zu (painting of hangon-kō)” in the Kudo-ji temple. The absence of legs became the standard hallmark characteristic of the depiction of a ghost soon thereafter. Prior to this time, ghosts had had legs, and not many of them were pretty.

At the bottom of this painting, one sees a large Chinese censer. The figure of a beautiful young woman appears in the smoke rising from it. She wears an elaborate kosode (short-sleeves kimono) decorated with shibori (tie-dye), and her uchikake (lined and quilted silk kimono) with a chrysanthemum arabesque pattern is tucked into her black obi belt with an arabesque. Her long hair is untied and hangs down loosely, and she is made up with white powder from her forehead down to her neck. The woman appears to be in the prime of her life, in a state of flowering beauty.

That is the image Emperor Wu saw, the image Li left him with, and it reflects what he wanted to see rather than the dead soul itself. When we reflect on why this beautiful woman floating out of the fragrance was made, it may have been to recall the mysterious story about her from faraway and exotic China. She may be the beautiful young wife that a man lost. Or, as in another version of this story that was popular in the Edo Period, she could be a courtesan a man longed for. The lady was loved, wanted, and yet fragile. The poem ends with the words:

We are lost with a beautiful woman in life

and even after death.

We are all emotional creatures.

We need to be wary of meeting a beautiful femme fatale.

We never know if the painter was referring here to the original poem or to another version,

but it is certain that the purpose of this painting was not to “cool people off” in the summer,

but rather to express sadness about a melancholic event in life.